The Washington Naval Conference and the Washington Naval Treaty

In the Shadow of the Great War: The Washington Naval Conference and Arms Control

The outbreak of war in 1914 surprised few observers. The great powers of Europe - Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Russia - had divided themselves into two alliances and nearly gone to war several times in the preceding twenty years. But the appalling destruction caused by the war and its horrific casualty rates came to dominate the postwar worldview of even the victors.

A significant contributor to the outbreak of war was judged to be the naval arms races that had sprung up between the great powers, and especially between Britain and Germany, in the first decades of the twentieth century. Germany as a rising world power sought to challenge the British Royal Navy’s dominance at sea, which pushed Britain towards an alliance with its longtime rival France. This in turn led to German fears of an overwhelming combined strike against its western front in the event of war with Russia (an ally of France), which provoked the assault on France in 1914.

To try and reduce the possibility of another arms race, the United States hosted a groundbreaking meeting between the major world powers of the postwar period. This was to be the first documented attempt at establishing an international arms control regime. It was known as the Washington Naval Conference

The Major Players at the Washington Naval Conference of 1921

The United States, United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Japan were the major naval powers that negotiated the Washington Naval Treaty. They were all members of the Allied powers which defeated the German led Central Powers in the Great War, and they were all major colonial and naval powers that maintained significant battle fleets.

The United Kingdom’s Royal Navy had long been supreme at sea, and had held it vital to maintain a fleet capable of taking on the next two largest naval powers simultaneously. As its colonial possessions stretched around the globe, it had to face the possibility of going to war with a European power like France or Italy aligned with Japan or even United States. Because of this, the Royal Navy maintained by far the world’s largest fleet - dozens of battleships and hundreds of smaller vessels. But all this came at a cost - primarily that other nations were driven to match that portion of Britain’s capabilities deployed near to them.

A successful Washington Naval Treaty would have to address this balance of power problem, and so the Royal Navy would inevitably suffer from any agreement. But, in return, the fleets of the other signatories would be restricted in size, reducing the number of ships Britain would need to maintain - a mutually beneficial result for all signatories and one judged to reduce the probability of conflict.

The synergistic nature of arms control caused it to be in each power’s interest to come to a limitation agreement. Italy needed to be able to be powerful in the Mediterranean, France had to be able to guard its home waters in the Mediterranean and Atlantic, Japan was intent on being dominant in the Western Pacific, and the United States maintained Atlantic and Pacific Fleets.

The Washington Naval Treaty: 1922 Marks the Start of the First Arms Control Regime

After much diplomacy lasting from late 1921 and into the spring of 1922, the major terms of an agreement were agreed upon:

Tonnage - Limiting the size/numbers of certain ships. Tonnage limits allowed a nation to choose to build fewer, more powerful vessels or more, less powerful vessels.

- Britain and the Unites States could each possess capital ships (battlecruisers and battleships) totaling 525,000 tons standard displacement, as well as 135,000 tons worth of aircraft carriers apiece.

- Japan would be accorded a total of 315,000 tons standard displacement for capital ships and 81,000 tons for aircraft carriers.

- Italy and France would each be allowed 175,000 tons standard displacement for capital ships and 60,000 tons for aircraft carriers.

No capital ship could displace more than 35,000 tons, and aircraft carriers

could only displace 27,000 tons. An exception to the aircraft carrier rule allowed a nation to possess two 33,000 ton carriers if they didn’t go over their total carrier tonnage allotment. Any ship larger than 10,000 tons was considered a capital ship.

Armament - numbers and sizes of guns carried:

- No capital ship could mount guns larger than 16" in diameter.

- Nothing but a capital ship could mount guns larger than 8" in diameter.

- No aircraft carrier could mount guns larger than 8" in diameter.

- No aircraft carrier could mount more than 10 guns with 6"+diameter.

- No adding a few aircraft to a battleship and designating it a carrier.

Effects of the Washington Naval Conference and the Resulting Washington Naval Treaty of 1922

The signing of the Washington Naval Treaty had an immediate impact on the naval shipbuilding programs of each signatory power. Britain was required to scrap a total of twenty eight capital ships, about half of which it had intended to keep in service. In addition, Britain had laid down the keels and hulls for almost ten new, ultra-modern capital ships which were now restricted by the Washington Naval Treaty. The G3 Battlecruisers and N3 Battleships were all cancelled. Britain built only two additional capital ships (excluding aircraft carriers), the battleships Rodney and Nelson, until the late 1930’s.

The United States also found itself with too many capital ships. The United States Navy was forced to cancel battleship and battlecruiser classes and suspend efforts to build the world’s most powerful navy. In fact, no battleship or battlecruiser was built by the United States for a full twenty years, largely due to the Washington Naval Conference. In an attempt to make use of hulls already under construction, the battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga were converted to the United States’ second and third aircraft carriers, both of which would serve in World War II.

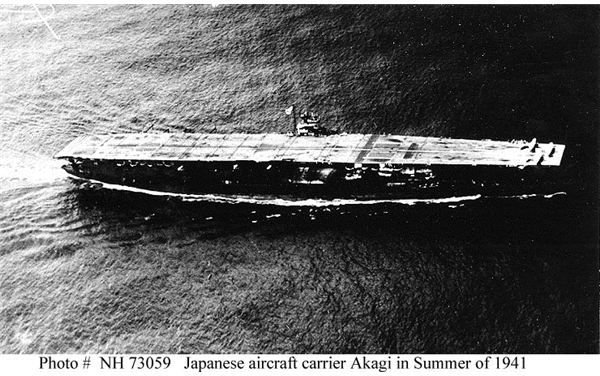

Japan suffered from the Washington Naval Treaty mostly in terms of politics. Its government was riven by pro and anti-treaty factions, and of all the signatories Japan was the most interested in pushing its boundaries due to its concerns about fighting wars with the United States or United Kingdom in the Pacific. It too had to convert two capital ship hulls to aircraft carriers, in its case the battlecruiser Amagi and its sister the Akagi. When Amagi was destroyed in an earthquake, the hull of the cancelled battleship Kaga was appropriated to replace it.

The Lead Up to the London Naval Treaty: 1930’s Contribution to Arms Control

Naturally the Washington Naval Treaty was, as a first effort in arms control, a bit spotty in places. It had a significant effect on two classes of ships: aircraft carriers and cruisers. The former were thrust into a position of importance in large part due to the fact that Britain, the United States, and Japan were at or near their capital ship limits from the day the treaty was signed. Aircraft carriers were the only large ships they could build, and although naval aviation was unproven as a military asset, it saw heavy development in the interwar period in part due to the Washington Naval Treaty.

When it came to vessels smaller than 10,000 tons - the largest of which were called cruisers by most navies - the lack of tonnage restrictions led to a veritable cruiser race between the naval powers. Japan in particular saw cruisers as a way to get past the tonnage restrictions placed upon it, and began building cruisers with ten 8" or fifteen 6" guns in addition to a

complement of incredibly powerful, long ranged torpedoes. Of course, to pack such quantities of firepower onto a vessel and still have it float hull sizes were increased, and with increases in hull size came displacement increases. Faced with a hard 10,000 ton standard displacement limit, Japanese designers began to pull a little creative accounting in order to officially stay within treaty parameters.

Naturally, once British and American intelligence agencies caught on they began producing cruiser designs that also pushed the treaty limits. But the arms control proponents of each power saw, in the sudden push to build cruisers, a need for an update to the Washington Naval Conference agreements - and so the London Naval Treaty was born.

The London Naval Treaty: Arms Control in an Increasingly Dangerous World

Though the Great Depression of 1929 onward put naval budgets in danger, arms limitations proponents felt it necessary to add some additional conditions onto the Washington Naval Treaty to mitigate certain shortcomings that had become apparent over the past eight years. So in 1930 the London Naval Conference was held, where after significant wrangling and near rejection on the part of Italy and Japan in particular, a few agreements were added to the naval arms control regime:

- Heavy Cruisers were defined as any cruisers mounting 8" guns. The US would be allowed eighteen, Britain fifteen, and Japan twelve.

- Light Cruisers were those mounting 6" guns, and while no hard numbers were mandated, tonnage limits were approximately 143,000 tons for the US, 192,000 tons for Britain, and 100,000 tons for Japan.

- Submarines could no longer mount cruiser size guns.

- Submarines had to surface and demand the surrender of targeted merchant ships, allowing their crews to take to lifeboats before their vessel was sunk.

Unfortunately for arms control proponents, a new war was around the corner. In 1936, the Washington Naval Treaty expired, and was not renewed. But while it lasted, the treaty did fulfill its purpose: for fifteen years, naval arms construction was limited and controlled, and it cannot be said that a naval arms race preceded or instigated the terror of World War 2.

Washington Naval Conference and Treaty Images and Sources

Sources:

Conference on The Limitation of Armament, hosted by ibiblio.org

Janes Fighting Ships of World War II, 1946 Janes Publishing Company, 1994 reprint edition

Steve Ewing, American Cruisers of World War II, 1984 Pictoral Histories Publishing Company

Robert C. Stern, U.S. Battleships in Action, 1980 Signal Publications

Images:

All images via Wiki Commons, Courtesy of the United Kingdom Government and United States Navy.