I Learned From That: Lack of Tool Safety Practices causes Chisel Job to go Awry

I had served four years as a marine fitter in Harland and Wolff Belfast, and left to finish my last year of apprenticeship at sea, which I carried out on deep-sea tankers before joining the ‘MV Fair Head,’ an Ulster Steamship general cargo ship.

The Fair Head loaded at Belfast, Dublin, Liverpool, and Glasgow before heading over the North Atlantic where we sailed up the St. Lawrence Seaway, discharging at Montreal and Quebec before going through numerous locks to other discharge ports on the Great Lakes which included Toronto, Hamilton, and Detroit.

Ulster Steamship prided itself as having one of their ships first up the St. Laurence Seaway after the winter ice had melted sufficiently on many occasions.

Anyway, I diverge; it was whilst in port that we carried out the main engine maintenance, renewing piston rings, changing fuel valves, air start valves, and cylinder heads. On our return sailing across the Atlantic to the UK we then overhauled the units we had replaced in port.

It was one such occasion that I had a narrow escape from a serious injury, whilst overhauling a cylinder head. This is an article about my experiences during my early years at sea as a young engineer, and how I learned from them.

We begin with a general description of the engine room of the ‘MV Fair Head.’

Engine Room Layout

Compared to the tankers I had sailed on, the engine-room was quite small and compact. The engine-room door opened from the accommodation and led to a maintenance platform area where we overhauled the cylinder heads and pistons, with the use of the overhead crane. There was a small workshop/store and I found out that as a newly promoted 4th engineer, the mechanical spares fell under my jurisdiction.

The next level down gave access to the scavenge doors, fuel pumps, and scavenge air inlets, before dropping down to the main plates where the normal pumps, generators, switchboard, and purifiers were located. Along the front of the engine were the explosion doors, cylinder lubricators, and the engine controls.

The engine was a two-stroke Werkspoor marine diesel engine controlled by a wheel that was rotated clockwise or anticlockwise, depending on an ahead or astern engine room telegraph order from the bridge. As the starting wheel was rotated air was supplied to the engine and once it was turning at the right revs, the wheel was further rotated to supply the fuel.

Maintenance of Main Engine Cylinder Head

Most of our maintenance was carried out in port; here we would replace a cylinder head or inspect the liners or piston rings for wear.

Cylinder Head Removal

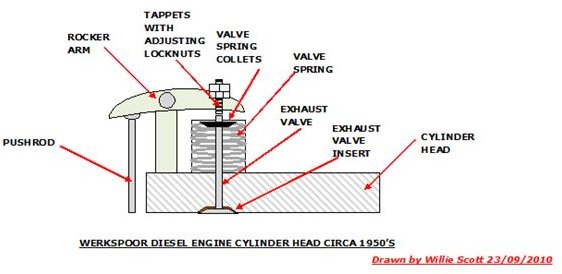

Removal of the cylinder head was pretty straightforward, with all the main bolting and studs being hydraulically tensioned and loosened. The air and diesel lines were disconnected and fuel and air start valves removed. The rocker arms were then disconnected and the head lifted off and set into a specially made maintenance stool for further inspection and dismantling of the valves.

Cylinder Head Overhaul

I usually did a couple of hours a watch on maintenance, so as soon as I had taken over the watch, I left the greaser at the controls and made my way up to the maintenance platform at the top of the engine room.

Once the cylinder head was removed and dropped into its maintenance cradle, it was a simple matter to remove the fuel and air-start valves, which were then put into a rack in the workshop for overhaul.

Back on the cylinder head, the valve springs were compressed and the collets removed, the valves were then marked for reassembly and withdrawn through the valve guides.

Every so often, there was a bad burn/gouge on a valve and insert seat that no amount of grinding would remove satisfactorily. I never did discover why this occurred, but suspected it was due to rocker clearances being too tight, allowing the valve lip to remain open when under compression/firing stroke.

The present remedy was to send the burnt valves ashore to be reground and to replace the valve insert and valve.

Replacing a Valve Insert - the Accident

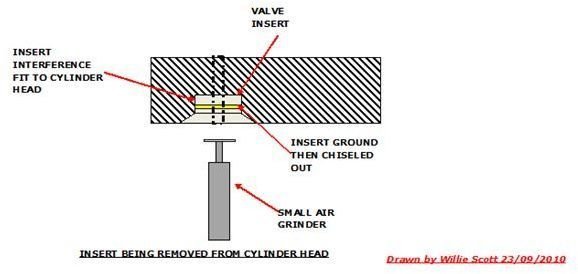

The insert was an interference fit into the cylinder head, so a groove was ground down so far into the insert as possible, and then it was chiseled out.

I had just finished grinding a groove as deep as I dared without going into the head. I now needed to chisel the rest of the insert. I hit the chisel head a few taps to line it up in the groove before giving it a well-aimed blow with the hammer.

I was instantly rewarded with a stinging sensation just above my left wrist, followed by a spouting of blood which splattered the bulkhead a good 3m away.

Shaking my head a few times, I banged the top plates a few times and the greaser came up to see what I wanted. He took one look at me swaying and wrapped a rag tightly around my wrist before bundling me through the engine room door shouting for the Chief Steward.(The Chief Steward was the ships first-aider)

Next: Operate on my arm with a sharp fish knife?

The Accident

The Steward appeared along with the Second Engineer, who told the greaser to stay with me and he would take over the watch, so I went off to the Steward’s cabin held up between him and the Steward.

The Chief Engineer appeared as if by magic and gave me a glass of Brandy, which I downed in one as by this time I was in shock and a lot of pain from my wrist up into my elbow.

The Steward asked me what had happened and as I was telling him he removed the rag from my wrist, gave it a few squeezes and applied a pad and tight bandage which stopped the bleeding. There was quite a large piece of metal buried in my arm just above my wrist and close to a number of blood vessels/veins; in fact he thought that the metal had probably nicked a main vein.

The Chief sent the greaser down to the engine room to get the chisel and to tell the Second I would not be back down on watch and that he (the Chief) would take over my next few watches to see how I got on.

The Captain had materialized from nowhere and after hearing the story again, wanted to have a feel at my arm, just as the Chief Steward had, and then they went into a confab in the corner.

The metal point had broken off the chisel and lodged in my arm, and as we were three days out of Belfast, our first home port, we had a few choices:

- As there was a distinct possibility of the metal point travelling up my arm, they could operate immediately and remove the piece of metal. This would entail using a razor-sharp fish-fillet knife belonging to the cook. Anesthetic and antiseptic would be large drams of rum or brandy, but they pointed out that the metal was close to major blood vessels, and was risky.

- Keep the arm well bandaged and keep an eye on the metal piece for movement. By this time I had a large black bruise emerging presumably from where the point of the chisel had penetrated my arm and it was throbbing like hell.

The captain and Chief went off to radio for advice and were back about ten minutes later after being in contact with a passenger ships doctor. His advice was to leave things as they were, keep an eye on the metal for any movement, and keep my arm strapped across my chest, high up to my right shoulder.

I was to stay in my cabin; no work or watch-keeping, and all being well the metal piece would not move any further up my arm and I could have it removed at a Belfast Hospital. However, if it did start to move then the Captain and Chief Steward would have no alternative but to slit my wrist and retrieve the metal.

Sketch of Werkspoor Cylinder Head

I Learned from That

Well, I never did find out how brandy or rum would act as anesthetic and antiseptic as the doctor’s advice was sound. We got into Belfast at 2am and an ambulance was waiting to take me to the Royal Victoria Hospital. Here they gave me a large jag of anti-tetanus in the rear end then froze my wrist and removed the chisel point which gave a rather satisfying ‘ping’ as the surgeon dropped it into a stainless kidney-shaped dish.

I carried this in my wallet for some time after the incident, and still bear the scar on my left wrist.

So what did I learn from that?

- Check cold chisels or hammers for cracks or burrs before using them; some of the old chisels and hammers I had used in the past could have done equal damage by splintering at the top end.

- Wear leather high-cuff work gloves when chiseling.

- Wear eye protection, this was drummed into me whilst serving my apprenticeship, and I could have lost an eye if the chisel point had not lodged in my arm.

- Have respect and faith in your senior officers and shipmates, the Chief Steward had done an extensive on-shore training in first aid and he and the Captain were prepared to take on a delicate operation in not ideal conditions. The Chief Engineer stood all my watches, and then kept me company when off-duty and, I had visits from the bosun, carpenter, and some of the mates and sailors.

All this happened nearly forty five years ago, and I remember it like yesterday. I have also remembered to wear gloves and eye protection when using a hammer and cold chisel ever since – even when using a bolster when laying concrete slabs in the garden; so be warned!